The Red Summer of 1919

It's been open season on Black people since this country was founded. During the 19th century, the worst of anti-Black violence was associated with the Southern plantation system, and the tradition of pointing to the South as the site of egregious racism persists to this day. But it's everywhere, and it's no surprise that the latest earthquake of racial unrest originated in what white Americans thought of as the "liberal" city of Minneapolis.

The eleven years of Reconstruction after the Civil War, a radical, misguided attempt to insure a modicum of racial equality and restitution -- for the former Confederacy only, of course -- only stoked the thirst of white Southerners for revenge when they were once again ceded control of their states. Between 1882 and 1930, 2,314 Blacks were killed in the South by white lynch mobs.

That's a lot of killing, especially when you consider that this was done in ones and twos. But there were larger race riots -- that is whites rampaging against Blacks -- as well: New York City in 1900, Atlanta in 1906. The Springfield, IL riots of 1908, where some 5,000 whites and European immigrants burned, looted, and destroyed, was so shocking to those who associated the city with the burial place of Abraham Lincoln that it led to the founding of the National Association of Advancement of Colored People.

But the Red Summer of 1919 witnessed the most widespread and sustained violence against Blacks in the history of our country. From April to November, some 30 riots broke out across the U.S., with hundreds of accounts of beatings, lynchings and the burning of churches and buildings. As a result of the violence, the Ku Klux Klan also saw a resurgence. Many factors contributed to this, but one of the big ones was a pandemic. The country was dealing with a third wave of the previous year's Spanish Influenza.

Last year marked the centenary of one of the bloodiest episodes of white America's racial paranoia, but who knows about it? Beyond a few news squibs and local segments for history buffs, nothing was made of it. A century ago, a pandemic-induced rupture of "normalcy" and fear created a wave of racial protest, but back then the current ran against African Americans. And so it seems appropriate that we underline the melancholy passage of anniversaries this summer and ask ourselves how and why this season of violence against Blacks got erased.

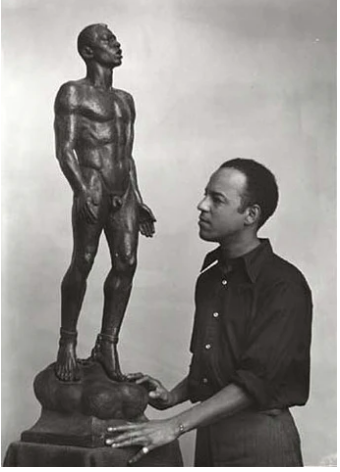

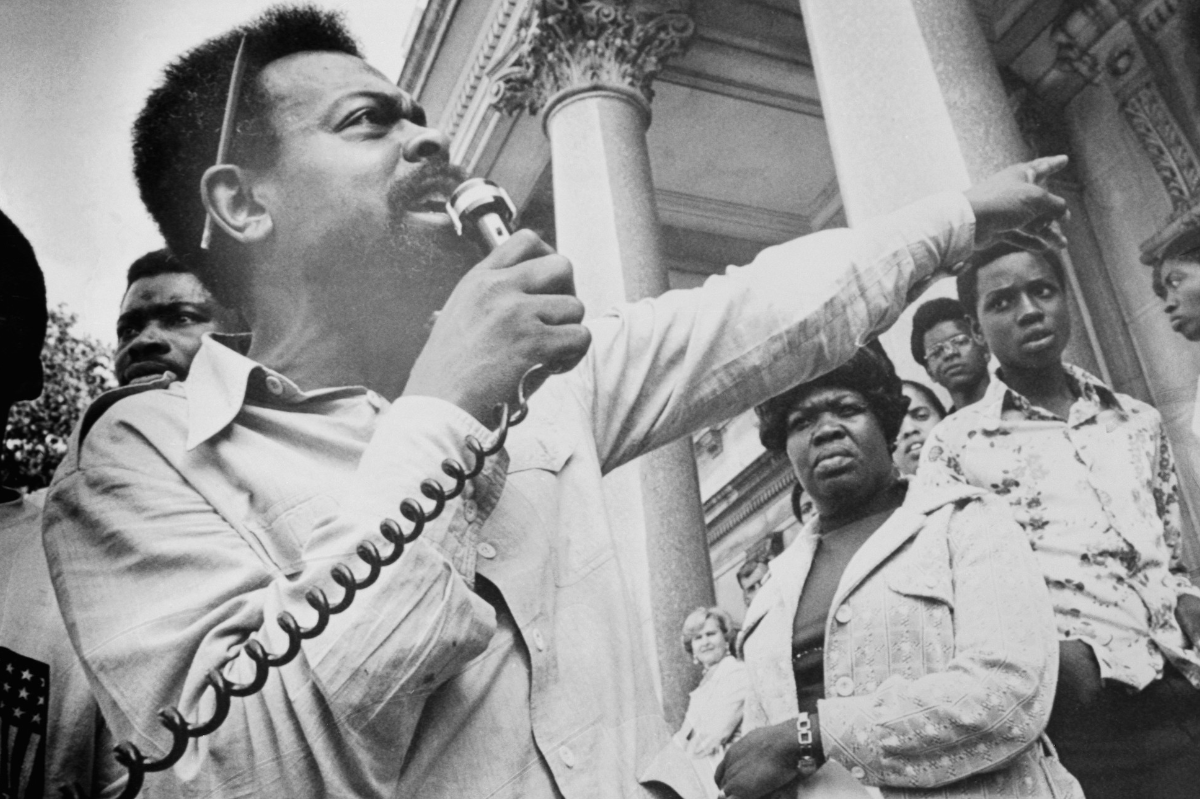

Some important writers of the later Harlem Renaissance contributed their voices of protest. Claude McKay first tasted fame as a result of the publication of his poetry of Black rage, most notably "If We Must Die." W.E.B. DuBois editor of The Crisis, the house organ of the NAACP, consistently thundered against the injustice, the oppression, the violence. James Weldon Johnson, then a field secretary for the same organization, coined the Red Summer label which needs to be much more widely known than it is.

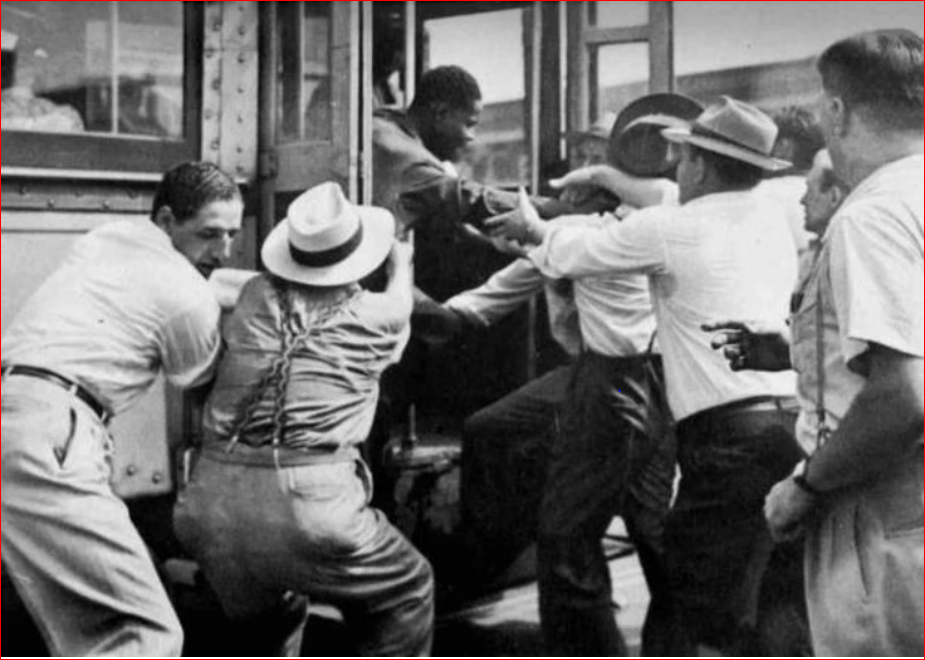

"[I]t was almost an impossibility for me," he wrote, "to realize as a truth that men and women of my race were being mobbed, chased, dragged from street cars, beaten and killed within the shadow of the dome of the Capitol, at the very front door of the White House."

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.