The Queer Harlem Renaissance and the Visual Arts:

Richmond Barthé

Of the many visual artists born at the turn of the last century who came of age during the Harlem Renaissance, only one has been pegged (no pun intended!) as unambiguously gay -- Richmond Barthé. Perhaps because of this odd underrepresentation (I mean, isn't any boy who dabbles in the arts under suspicion?), the visual arts haven't figured much, or at all, in any inventory of the Queer Harlem Renaissance. (Not that there's been such an inventory, but rest assured, it's coming!)

Two things to note about the visual art of the Harlem Renaissance. 1) It was a late-comer to the party, gathering momentum in the late 20s and continuing into the 30s. By contrast, the Great Depression had almost snuffed out the literary efflorescence of the Renaissance. 2) Because a Parisian apprenticeship was practically de rigueur for these artists, there was much less cohesiveness among them -- different artists got to Paris at different times for different lengths of stay. There was no "movement," no unity of style, no anointed leader. It wasn't even that New York-based. The one organization, the Harmon Foundation, that almost accidentally ended up nurturing and promoting the artists of the Harlem Renaissance was founded by a white real-estate developer with no interest in art and ran under the iron guidance of a white lesbian, Mary B. Brady.

As Barthé's name indicates, he was descended from Louisiana gens de couleur, even though he was born (1901) and spent his childhood in nearby Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. New Orleans was the Big City in that part of the world and there he went in his later adolescence, where he entered the toxic embrace of the Catholic church, which encouraged his artistic development (Friar Harry Kane raised money for him to undertake studies in fine art) and infected him with a lifelong crippling guilt about his sexual orientation.

Barthé's drive and talent eventually brought him to the heart of the Harlem Renaissance via a four-year curriculum at the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago was where he gained recognition as a sculptor, but in 1930, he established his first studio in Harlem and went on to become one of the most successful African American artists of the next two decades.

Like any good artist, Barthé was a mass of contradictions. His art was clearly Afrocentric yet he was impatient with critics who pointed this out. Even though he enjoyed access to and friendship with the leading lights of the Renaissance, he moved to Greenwich Village after his first year. Success followed success but several demons drove him from the site of his greatest acclaim to live as an expatriate in Jamaica from 1950 to 1970.

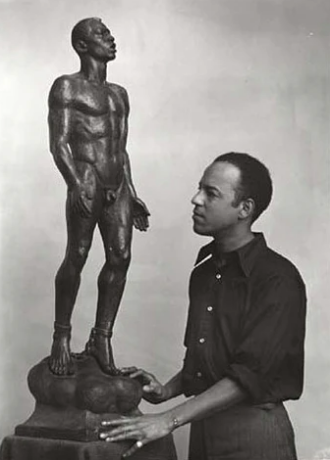

Firstly, although he was a superb sculptor, the winds of artistic fashion (realism -- so passé!) turned against the human bodily representation that inspired his art. He couldn't or wouldn't shift from the early style that had brought him such success. His queer sensibility also wedded him to the human form. The homoeroticism of his male nudes is so blatant that most commentators won't even talk about it. (The statue in the photo above was the final model of a James Weldon Johnson Memorial that Carl Van Vechten tried to get the City of New York to erect. In this one instance, the queer eye, trying to leverage the classical tradition of the male nude, couldn't overcome the shocked objections of the Black bourgeoisie and the city's civic leaders.)

Also, his homosexuality brought him little joy. Handsome, talented, ensconced within the largest, most active gay population of the time, he had only fleeting affairs of which we know little. He and Richard Bruce Nugent were an item for a hot minute, but Nugent wasn't cut out for monogamy. Barthé fell in love with one of his African American students, but the guy was straight and couldn't reciprocate. Alain Locke undoubtedly came onto him and, generous of spirit in the rejection he so frequently encountered from the objects of his desire, Locke became Barthé’s friend and confidant. It was in a letter to Locke that Barthé confessed his desire for a long-term relationship with a "Negro friend and a lover." Barthé’s preference for Black men made the small pool even smaller. Nor did an ingrained internalized homophobia, courtesy of the Catholic church to which he was devoted all of his life, move him towards a more liberated stance.

We can only speculate about what kinds of erotic adventures Barthé may have experienced once he became an expatriate. Jamaica was -- and is -- a deeply homophobic society. As the years passed, Barthe's reputation and financial resources diminished. However, his undiagnosed and untreated mental condition grew to the point where, after twenty years in Jamaica, he abandoned his home and undertook a peripatetic life in Europe for the next seven years.

In 1967, he washed up on the shores of my hometown, Pasadena, California, where he lived until his death in 1989. The decades of his greatest fame were long past, and there was no miraculous revival of his artistic reputation. Sick, elderly, and impoverished -- and incapable, apparently, of soliciting African American support (Pasadena was not the place to find a vibrant Black community) -- Barthé would have suffered a far worse and shorter final act had it not been for the unlikely friendship of actor James Garner (not gay) who became his benefactor and advocate. (Barthé's last sculpture was a bust of Garner as Maverick.)

Richmond Barthé was the first African American artist, along with Jacob Lawrence, to have his work acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1942). He was important then, and he is important now, not least to the queer community that can celebrate dozens of white artists of the mid-twentieth century but few Black ones. His art is profoundly moving and beautiful -- and sometimes sexy AF! C'mon, boys! Swap out your tired statues of Michaelangelo's David for Barthé's Stevadore.

I might have seen Barthé somewhere in downtown Pasadena, although, in my salad days when my years were young and green, I would have taken no cognizance of an elderly Black man. Somehow Pasadena recognized the artist who had chosen the city as his final residence and renamed the street where he lived Barthé Drive. New Orleans, Atlanta -- take the hint!

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.