"Looking for Langston" - The Peerless Ancestor

The 2017 edition of Frameline, the San Francisco LGBT film festival, screened a gorgeously restored copy of Issac Julien’s Black queer classic, Looking for Langston, released during the Stone Age of queer cinema – 1989. Hard to believe it is already a quarter of a century old. I had seen it many years ago, but in the greenness of my years, I had little taste for non-narrative films, and Looking for Langston was nothing if not experimental. Seeing it now with a greater understanding and (presumed) maturity, I can only add my voice to the mountains of accolades the film has already accrued--among them a Teddy award at the Berlin International Film Festival.

Although the film is non-narrative, there is a thematic and visual cohesion that makes it enjoyably watchable througout its 40 minutes and suggestive enough to sketch possible story lines in my mind as I think about it later. Sumptuously shot in black and white, the film begins with a funeral, presumably Hughes’ though, as an in-joke, it is Julien who lies in the coffin, and a voice-over of Toni Morrison’s eulogy of James Baldwin. If we take the funeral to be in commemoration of, at its most generic, a Black queer artist, then the camera’s descent into a highly stylized gay Harlem nightclub where most of the action takes place can easily be read as symbolic or Freudian or deconstructionist . . . or any number of ways.

The thing that strikes me about Looking for Langston is at what a high point Black queer filmmaking begins. Oftentimes – and I’ve seen this with other oppressed minorities finding their voice – the filmic beginnings are raw, amateurish, and focused on the difficulties of being (fill in the blank). Witness the movies of Oscar Micheaux, who never made a film that measured up to what Hollywood was producing during that same era. Similarly, as the first feature-length film featuring a gay Black man growing up in the ‘hood, Moonlight deserved its Hollywood coronation as Oscar’s 2017 Best Picture. So sometimes a fully fledged artists comes shooting out of the gate and needs no ancestors on whose shoulders (s)he can stand. But that’s a rarity and a quirk of history. When considering top-flight movies featuring Black queer characters, what else comes to mind? Dee Rees’ Pariah (2011) is workmanlike and adequate but not a masterpiece. (Cheryl Dunye’s Watermelon Woman [1996] is much more interesting.)

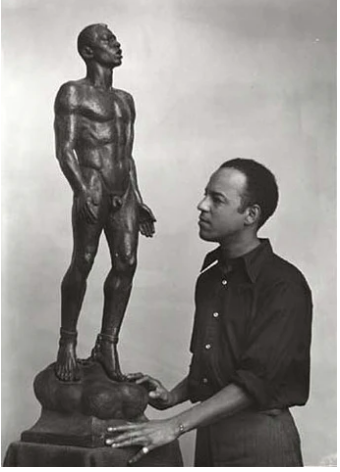

As somebody who is currently working on a documentary about queers in the Harlem Renaissance, I was particularly interested in the film’s visual and literary references – recognized much of the archival footage used (and which I plan to use myself) as well as the literary texts quoted. In fact, the world that Julien creates in Looking for Langston is so compelling that there were external clips that threw me out of it. The footage of Hughes reading from Montage of a Dream Deferred to a jazz band in the background now seems corny, and the voice-over excerpts of Essex Hemphill’s sexually explicit poetry (“Now we think/as we fuck/this nut might kill us”) struck me as vulgar given the era’s sophisticated sheen. I can’t imagine anybody in Langston’s circle ever saying “fuck.” I also didn’t realize, until doing further research, that the white character was “supposed” to represent Carl Van Vechten, that the handsome mustachioed lead was “supposed” to represent Langston himself, and that the hunky dark love interest was an imagined male lover named “Beauty.” (See above photo.) Nor did it matter.

Many people know that there used to be copyright disputes with the Hughes’ estate requiring that the sound be turned down or off during the two clips of Hughes’ reading from Montage. I believed, as did many, that was because the inheritors of the Hughes estate didn’t want to have his name explicitly associated with queer themes, but, as Wikipedia points out, the estate allowed Hughes’ poetry to be included in many anthologies of queer poetry. So it seems that the original difficulties, now ironed out, weren’t due to denial or homophobia on the part of the protectors of Hughes’ reputation but stemmed rather – and predictably--from the usual greed of the rights holders.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.