The Inescapable Blackness of Jean Toomer

(And the Escapable Jewishness of Waldo Frank)

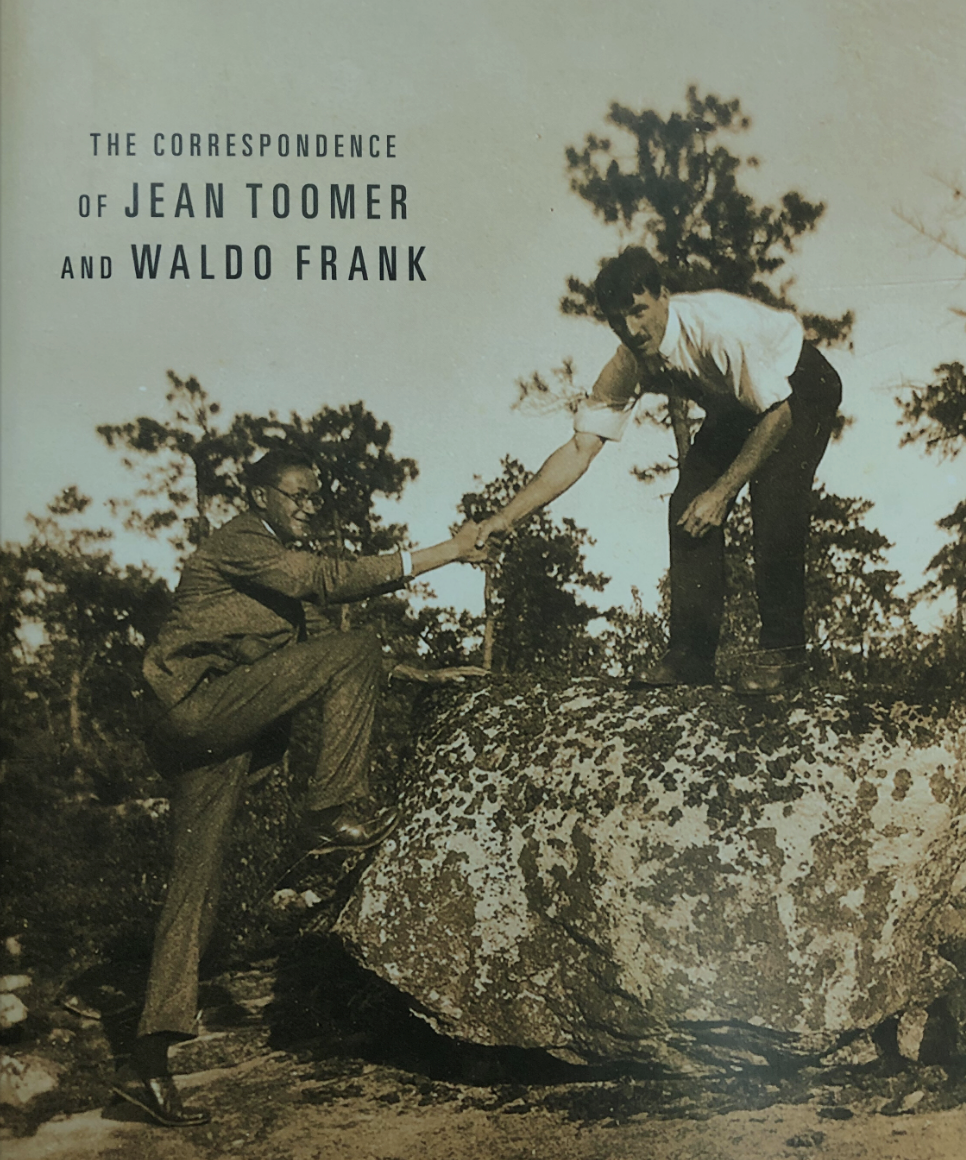

In the fall of 1922, two young American writers, Jean Toomer and Waldo Frank, traveled together to Spartanburg, South Carolina, for research on novels that both were writing at the time. Toomer, of mixed ancestry, was oftentimes light enough to pass for white but did not wish to do so on this particular occasion because his subject was Negro life in the rural South. Waldo Frank was a Jewish writer, famous at that time in modernist circles, who had also conceived of a novel (“Holiday”) that dealt with race in the Deep South. Through the medium of a literary correspondence (Frank lived in New York; Toomer, Washington, DC), they discovered themselves to be kindred spirits, striving to bring about the upheaval of spiritual yearning and frustration below the surface of ordinary life.

Although Toomer was beginning to get his short pieces and poetry published in the little magazines that promoted modernist writing, Frank had already published a psychoanalytic novel – an innovation for the time – and had two more modernist experimental novels in the works, as well as being an associate editor of the influential Seven Arts journal. During their brief but intense friendship, Frank not only guided Toomer through the composition of “Cane” but brought the manuscript to his own publisher of Boni and Liverwright. (Horace Liverwright was one of the Jewish upstarts, along with Alfred Knopf, who forced upon the hidebound publishing world the writings of Negroes and modernists, but that is another, although related, story.)

Waldo Frank’s imprint is visible in “Cane.” Not only did he write the Introduction, but Toomer dedicated its longest section, “Kabnis,” to his friend. As “Cane” was being published in 1923, Frank managed to bring his friend to New York City to live the literary life in Greenwich Village. And so Toomer did but soon became disenchanted with the egos and quarrels and clashes. More significantly, however, Toomer wanted to go beyond mere literature and conceived of himself not as a writer but as a spiritual seeker. He soon fell under the influence of the Russian philosopher, mystic, and spiritual leader George Gurdjieff and wrote out of that worldview until the mid-1930s. It was a worldview that transcended race, and that was, for Toomer, part of its appeal.

As a light-skinned African American, Toomer had spent his life crisscrossing the color line – Black in DC, where he had grown up the grandson of a famous Black politician, white in other places where he traveled for education (the midwest) and as a young man finding himself. When he spent four months in Sparta, Georgia as a substitute principal in a Black school, he tapped a current of creativity that spurted out the astonishing sketches and poems that were later collected in “Cane.”

It was a one-off, but what a one-off! American writing was producing other High Modernist classics from that period (“Winesburg, Ohio” by Sherwood Anderson, “Spoon River Anthology” by Edgar Lee Masters), but “Cane” was the first to treat of African American life. The irony was that Toomer was the first Black author who did not believe that Black ancestry made him Black.

He grudgingly gave his approval to have “Cane” marketed as a Negro novel but quickly came to regret it. As he wrote to his publisher, "My racial composition and my position in the world are realities that I alone may determine.” It wasn’t true, but he refused to accept it. He held himself aloof from the burgeoning Harlem Renaissance of the later 1920s – or rather engaged with its writers only as a teacher of Gurdjeffian philosophy. He had gone beyond writing and never published anything of significance again.

Although Toomer was, in appearance, racially indeterminate and tried to retreat into the anonymity of Quakerism in the Midwest, his subsequent marriages to white women ignited anti-miscegenation firestorms in newspapers and magazines. In a final historical irony, Toomer became acclaimed as a great American writer because “Cane” was rediscovered (and appreciated in a way that it had not been at the time of its publication) as part of the reclamation of African American literature spurred by the celebration of Black consciousness in the 1960s.

And what of Waldo Frank? After his friendship with Toomer ended in 1923, Frank went on to have a productive, influential career in journalism, leftwing politics, and, most importantly, as a cultural ambassador between North and Latin America. He continued to write novels, sometimes with Jewish characters (“Summer Never Ends", 1941) and even published “The Jew In Our Day'' in 1944. However, Frank was never defined or circumscribed by his Jewish ancestry. The novel that he was researching during his trip to the South with Toomer was published shortly after “Cane” and disappeared quickly, an unrevivable failure. Dying in 1967, Frank lived long enough to know about “Cane”’s remarkable efflorescence of literary glory, but what his reaction may have been to the book in whose making he had played such a significant role remains unknown – or at least subject to further research. Even as a putatively Jewish writer, Waldo Frank is all but forgotten.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.