The First White Promoter of the Blues

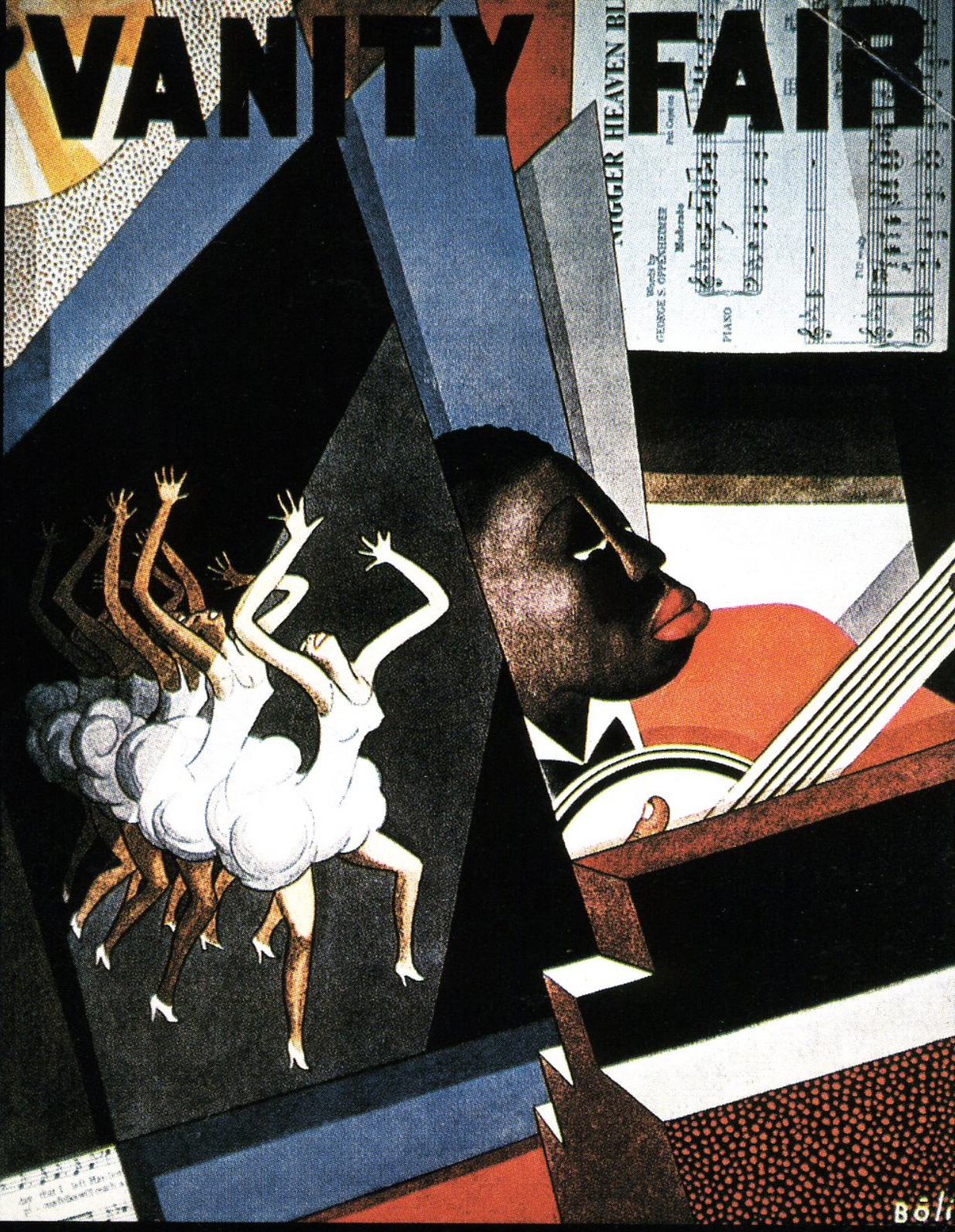

Before there was the record producer John Hammond (not to be confused with the white blues musician John P. Hammond), before there was the British Invasion of the 1960s, there was (sigh) the music and dance critic, successful light novelist, socialite and tastemaker Carl Van Vechten who, during the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance in 1925 and 26, introduced the blues to white America. This he did through several articles in Vanity Fair, the monthly magazine of popular culture that exposed Americans outside of New York to trendy topics, modern graphics, and a tone of humorous cynicism.

The first of these articles, "The Black Blues" (August 1925) stands up remarkably well even a century later. Van Vechten had immersed himself in Harlem culture and was nothing if not a quick study. Also, being a music critic of long standing, he appreciated and explained the technical aspects of the genre -- the pentatonic scale, the improvised vocalizations, the innovative combinations of instruments. "Notwithstanding the fact that the musical interest ... is often of an extremely high quality, I would say that in this respect the Blues seldom quite equal the Spirituals. The words, however, in beauty and imaginative significance, far transcend in their ... poetic importance the words of the religious songs. They are eloquent with rich idioms, metaphoric phrases, and striking word combinations."

Van Vechten goes on to quote, with attribution, assessments of the blues culled from personal communications with W.C. Handy and Langston Hughes. The passage from Hughes' letter to Van Vechten has become foundational. "The blues always impressed me as being very sad, sadder even than the Spirituals, because their sadness is not softened with tears, but hardened with laughter, the absurd, incongruous laughter of a sadness without even a god to appeal to."

Why the sigh preceding the introduction of Van Vechten earlier? Van Vechten was a complex and contradictory character. His "discovery" of Harlem in the 1920s and the good-faith efforts he exerted to publicize what was then known as The Negro Renaissance were both extraordinarily fruitful (he secured the publication of Langston's first book of poetry, The Weary Blues) and, in certain instances, quite toxic. The most bedeviling instance of Van Vechten's impact was the 1926 publication of his novel, Nigger Heaven, and this also involved his literal appropriation of the blues, although the title of his book was so incendiary that the inclusion of actual blues lyrics without permission might have seemed like a minor infraction except for the threat of lawsuits following its bestseller status.

In a panic, Van Vechten asked his friend Langston to quickly come up with substitute blues lyrics for subsequent printings, and the young poet complied. Although that staved off legal action, Langston's evident support couldn't entirely mitigate the public relations disaster amongst the Black intelligentsia occasioned not only by the title but by Van Vechten's pulpy and sensationalistic depictions of Harlem's nightlife. (The novel begins with the lurid doings of a pimp known as The Scarlet Creeper.) Although W.E.B. DuBois scathingly reviewed the novel as "a blow in the face" and "an affront to Negro hospitality," that didn't hurt its popularity amongst the white readership, and Nigger Heaven was by far the most commercially successful of Van Vechten's novels.

But we have strayed somewhat from Van Vechten's championship of the blues, a cultural stance far ahead of its time, not only for a white man but for many African Americans as well. In an astute comparison with the recuperated status of the Spirituals during the 1920s, he writes of the blues, "The humbleness of their origin and occasionally the frank obscenity of their sentiment are probably responsible for this condition [of being looked down upon]. In this connection it may be recalled that it has taken over fifty years for the Negroes to recover from their repugnance to the Spirituals, because of the fact that they were born during slave days. Now, however, the Negroes are proud of the Spirituals, regarding them as one of the race's greatest gifts to the musical pleasure of mankind. I predict that it will not be long before the Blues will enjoy a similar resurrection which will make them as respectable, at least in the artistic sense, as the religious songs."

He was right about that. Fifty years after the publication of his appreciation, the genre's conquest of new audiences amongst urban Blacks (the Chicago Blues) and its fervent embrace by white British and American rockers (the Rolling Stones, the Beatles) sealed its status as one of the most creative and consequential contributions of African American culture to the world.

(Queer nota bene. Van Vechten's next Vanity Fair article on the subject, "Negro 'Blues" Singers," [March 1926] profiled Ethel Waters, Bessie Smith, and Clara Smith -- all bisexual women.)

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.