The Evolution of "Fi-Yer," Part Two

Langston Hughes published "Fire" in his first collection of poetry The Weary Blues.

Here is the poem in its entirety.

Fire, Fire, Lord! Fire gonna burn ma soul! I ain't been good, I ain't been clean — I been stinkin', low-down, mean. Fire, Fire, Lord! Fire gonna burn ma soul! Tell me, brother, Do you believe If you wanta go to heaben Got to moan an' grieve? Fire, Fire, Lord! Fire gonna burn ma soul! I been stealin', Been tellin' lies, Had more women Than Pharaoh had wives. Fire, Fire, Lord! Fire gonna burn ma soul! I means Fire, Lord! Fire gonna burn ma soul!

The speaker echoes the traditional Christian understanding that sinners will go to hell and burn forever. With radical honesty the man acknowledges his evil nature and that fire is his inevitable fate. But he asks a question, "Tell me brother, do you believe, if you wanna go to heaven (you) got to moan and grieve?" The implication is that perhaps the life of constricted virtue leading upwards is not worth the price of foregoing pleasure and sin. In any event, the man has made his choice and accepts his place in the Christian afterlife.

When Hall Johnson sets this text to music, he erases all doubt or ambivalence. He repeats the initial stanza again and again and replaces the glimmer of pleasure in the original poem ("Had more women/Than Pharaoh had wives.") with further confirmation of eternal damnation: "Tell me, brother, can't you see/Dem fiery flames wrapped all 'round me." The final extended high note on which the song ends can easily be sung as a wail of despair.

Nugent introduces "Fi-Yer" realistically towards the end of "Smoke, Lilies and Jade" when his autobiographical protagonist, Alex, attends a classical performance in a church with Beauty. "Fy-ah Lawd had been a success . . . Langston bowed . . . Langston had written the words . . . Hall bowed . . . Hall had written the music." But the obsessively repeated lyric, "fire's gonna bu'n ma soul," becomes a leitmotif that sounds throughout the scenes leading to the openly gay embrace. The fire of damnation has become the fire of passion.

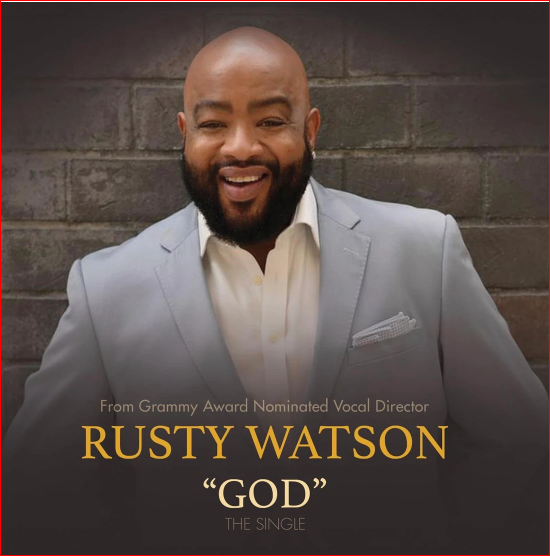

Rusty Watson's powerful delivery nicely plays on this admixture of exaltation and despair. Hall's so-called modern spiritual can easily be flattened to a fatalistic acceptance of damnation. Nugent places it in positive context, transforming (perhaps) the Christian trope of fiery damnation into the ecstacy of physical passion. Rusty frees "Fi-Yer" from its art song origins and injects his mastery of gospel into his interpretation. His final soaring "s-o-o-o-u-u-l," the note that pushes Alex into a spontaneous manifestation of his love for Beauty, is overwhelming -- yet ultimately ambiguous.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.