The Early Death of “Smoke, Lilies and Jade”

Part One

In 1926 a precocious 19-year-old poet and artist, Richard Bruce Nugent, penned the first positive depiction of same-sex desire in American letters. Looking back, this seems like an epochal achievement, and it issued from the heart of the Harlem Renaissance.

The Renaissance suffered a decline in reputation shortly after it was economically crushed by the Great Depression and the taste for literature and art shifted towards protest, a critique of capitalism, and, for Black artists, less kowtowing to white patrons. Eventually the cultural production of the Harlem Renaissance was rediscovered and canonized to some degree by different constituencies of the cultural and educational establishments. Langston Hughes had never gone into eclipse because of his lifelong prolific writing, but feminism had to uncover the grave (and the genius) of Zora Neale Hurston. The Black Arts Movement was partial to Claude McKay, and rising Black stars in academia, such as Henry Louis Gates and Houston Baker, raised Jean Toomer’s stock as well as providing sophisticated analyses of the Renaissance oeuvre.

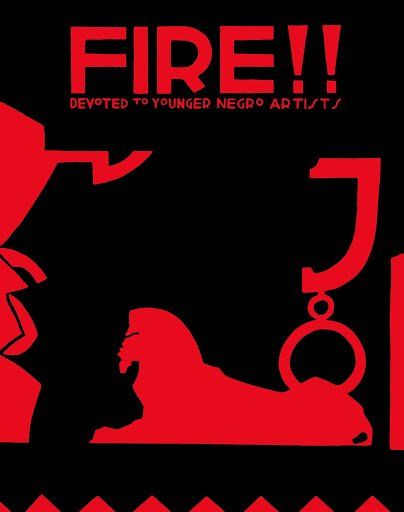

Picked over as the Renaissance was, nobody knew about “Smoke, Lilies and Jade.” This avant-garde prose poem appeared in a single issue of the arts journal Fire!!, and both the stream-of-consciousness style as well as the objectionable subject matter raised the hackles of the old literary guard. Nugent’s contribution was only one of many provocations brandished by the magazine’s editor, Wallace Thurman. (Thurman actually hoped the magazine would be banned in Boston thus raising its notoriety, but that didn’t happen.) When Fire!! appeared in November of 1926, it was either denounced by Black reviewers or pointedly ignored. Few copies were sold, and a real fire consumed most of the print run. Nobody appreciated Fire!!’s astonishing literary and artistic qualities, and one of the Renaissance’s signal achievements literally went up in smoke.

Until, that is, a gay white chemistry professor, Thomas Wirth, became a collector of Black literary memorabilia while teaching at HBCUs during his professional life. Wirth was particularly fascinated by the Harlem Renaissance, and in the late 70s he was introduced to Nugent, then living in Hoboken and one step away from homelessness. Wirth and Nugent became friends, and when Nugent showed Wirth his one personal copy of Fire!!, the chemistry professor turned publisher and founded Fire!! Press in 1982 using plates made from Nugent’s original issue to put reproductions of the magazine back out into the world.

As the gay liberation movement picked up steam, Nugent was occasionally approached, not as a foundational creator of a queer aesthetic, but as one of the few living witnesses of the Harlem Renaissance. Jewelle Gomez, who worked on the 1984 documentary Before Stonewall, says that Nugent was a recalcitrant informant, never even admitting to being gay, and in his brief appearances on screen he says nothing particularly insightful or enlightening. The producers and directors of Before Stonewall didn’t know what they had before them, and Nugent was never one to boast of his accomplishments. “Smoke, Lilies and Jade” remained an unknown masterpiece, but that was all about to change.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.