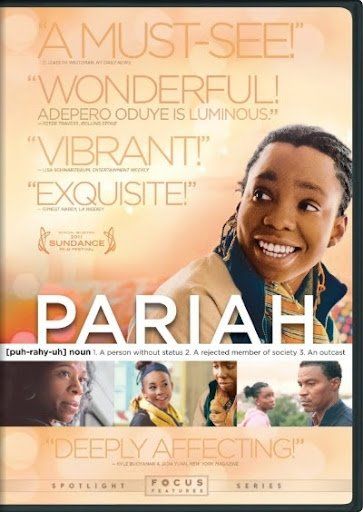

Pariah - A Narrative of Black Lesbian "Firsts"

Pariah means outcast. The film, Pariah, follows the development of Alike, a seventeen-year-old high school student in Brooklyn struggling to hide her sexual orientation from her family and her family’s friends. Unlike her best friend, Laura, a “butch” lesbian (or AG as they’re referred to in the film, AG meaning “aggressive”), Alike has a hard time finding her place not only in the straight world but in the gay world which she is just beginning to explore.

Throughout the film, I was struck by Alike’s loneliness and her desire to be accepted despite her insecurity about where she fit into the two worlds she was trying to negotiate. From the very beginning, the first scene of shots at a lesbian club, Alike is shown as cut off despite being with her best friend in a sea of people. Alike literally changes her identity (for others) by changing her outfits, shedding the girly clothes her mother makes her wear to the more masculine ones of an “AG.” She borrows these clothes or buys them from Laura, a straight-up butch, who is studying for her GED, and working to pay bills while living with her sister who is also working.

Although the film clearly makes Alike the protagonist (the director, Dee Williams, is herself a Black lesbian), other characters are presented sympathetically with the possible exception of Audry, Alike’s mother, a devout Christian. Audry is shown trying to reach out to Alike in a number of ways and is hurt by Alike’s refusal to communicate with her and the rejection of the wardrobe she buys for her. Although she never utters the word “lesbian,” she makes clear her dislike for Laura who she believes is leading her daughter down the wrong path. Audry’s Christian homophobia makes it impossible for her to maintain a supportive relationship with Alike once she comes out to her family.

By contrast, Alike has a better, more nuanced relationship with her father, a policeman who is shown to be having an affair with another woman. (This is one plot point that never gets developed but acts as the catalyst for the family fight that outs Alike. Interestingly enough, it is the mother who finally puts out in the open all of the family’s secrets – not only her husbands’ affair but her daughter’s homosexuality. And it is her mother who physically attacks Alike.) There are moments in the film where Alike is shown to be “daddy’s little girl” and actually enjoys that loving bond. But Carl, Alike’s father, is blinded to Alike’s lesbianism by the kind of love he has for the daughter he wants, not the daughter he has. He is shown accepting the prevailing homophobia of his community when he remains silent as a friend of his taunts Laura in a corner store by calling her a “bulldagger.” And I’ll be the first to admit how disappointed I was that Alike’s father didn’t teach him a lesson after the man implied that Alike was a lesbian.

Although Alike’s struggles are well documented in the film, aspects of her relationships with others seemed a bit sketchy or even stereotyped. Sharonda, Alike’s younger sister, actually knows about Alike’s lesbianism and sometimes threatens to tell their parents, although it’s clear that there is a loving bond between the two. When the parents fight downstairs, Sharonda seeks emotional protection by getting into Alike’s bed. It’s touching to see the sister’s cling to one another while their parents’ marriage is flying apart. Yet I would have liked to see that relationship blossom – Sharonda is the only person in the family who knows the truth about her sister. I couldn’t help but wonder what sort of relationship they would have after Alike was kicked out of her house by her mother. It was interesting that the film presented three family members with different levels of knowledge and acceptance: Carl, who is in active denial; Audry, who knows but refuses to accept; and Sharonda, who both knows and accepts.

Pariah is the first narrative film to feature a Black lesbian, and I was proud that the film was as well-done as it was. I thought it was interesting that Dee Williams chose as her protagonist a young woman closeted to her family, out to her friends, and yet still so inexperienced and unsure of herself. During the course of the film, however, Alike does come into her own, not only accepting her lesbianism but using her love of language and intelligence to distance herself from her home community. At the end of the film, Alike is on a bus bound for Berkeley, California where she has a scholarship. Berkeley here is presented as a site of freedom from the constraints of a homophobic community.

Yet I didn’t love everything about Pariah. I found myself irked by some aspects of the friendship between Alike and Laura. The script plays on the idea that Laura may have serious feelings for Alike, which itself leans on the notion that best friends tend to have borderline love-like feelings for each other. Their relationship is interesting but I wish that the director would have made it not so typical and easy to read. In the few movies I’ve seen with a lesbian character, the best friend often falls in love with her, but that doesn’t happen much outside the movies. Oftentimes the story seemed rushed; I wanted more time on the intimate moments Alike shares with the people around her. I also wanted a bigger view of the larger black LGBT community. I wanted to see how Alike would react to some of the hardships that an out person goes through, which was shown but not as much as it should have been.

However, no movie is perfect, and this film attempted to show different sides of “the life” while staying true to some of that things that one may experience being out and being closeted. I was pleased to see a theatrically released feature film about a Black lesbian with such strong acting, good script and high production values.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.