Nella Larsen Gets Dragooned Into The Queer Harlem Renaissance

The literary lesbian output of the Queer Harlem Renaissance provides meager fare: a couple of windy, antique love poems by Angelina Weld Grimké; certain passages in Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s private journal not meant for publication. That’s it. Compared to the blaring boastfulness of lesbian and bisexual women singing the blues, these strangled yelps are pitiful indeed. Patriarchy, white and Black, made every effort to stifle women’s voices; the higher the class, the more effective the muzzle.

Nonetheless, literary women of talent found ways to critique and skewer systemic male privilege, most notably Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larsen. Larsen’s two novels, Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929), provide a “thick description” (to use a social science term) of the complex, shifting terrains that Black women of ambition and intelligence had to negotiate. Although respectfully reviewed at the time, they didn’t sell well and slid into the dustbin of history. Larsen’s writing career was amazingly short and ended disastrously with accusations of plagiarism. Larsen herself shied away from the spotlight and was not a good publicist for her art. Besides, what weighty and significant interest could “women’s writing” hold for posterity?

All that changed with the recovery of women’s literature in the wake of the second-wave feminism that transformed culture, academia, and public discourse in the 60s and 70s. The writings of Hurston and Larsen, having languished in obscurity for decades, entered the canon of American literature through the recovery efforts of African American and feminist literary critics.

And then, in the case of Passing, a lesbian subtext was teased out, cogently argued by Deborah E. McDowell in her hugely influential introduction to the 1986 reprint of Larsen’s novels. Thousands of students read it in hundreds of courses on Black writing or feminist writing or both. From that point on, Passing was received as a lesbian or proto-lesbian classic.

Now here is where things get interesting. Larsen’s biography is complicated and bursting with jostling contradictions to be sure, but no whiff of same-sex attraction emanates from its surface. Of course the patriarchy hurt her, and the men in her life – especially her husband -- were disappointments, but what else was new for a woman of her race and generation? If Larsen “revealed” her lesbian tendencies in her writing, it took over half a century for anybody to notice.

And what was there to notice? McDowell’s interpretation is solidly grounded, especially to those of us, children of the New Criticism, who have been trained in the art of close reading, but the homoerotic subtext didn’t leap off the page in the manner of, say, Nugent’s “green and purple story . . . in the Oscar Wilde tradition,” to quote Langston’s description.

Nonetheless, and even though it is based on an interpretation, Passing is now regarded as a queer achievement of the Harlem Renaissance. That is why Time Magazine pegged its belated discovery of the Queer Harlem Renaissance to the film’s Netflix debut and that is why NewFest screened that same film as a Centerpiece offering.

I’ll take it because there’s not much else to take on the distaff side of the literary queer Renaissance. But what about Larsen herself? Let us say that she wrote a queer novel. That doesn’t make her queer nor does it make her a “queer icon.” Blair Niles was a white woman who published a novel with a sympathetic gay protagonist just two years later (Strange Brother), yet nobody is fighting to enroll her into the ranks of queer icons.

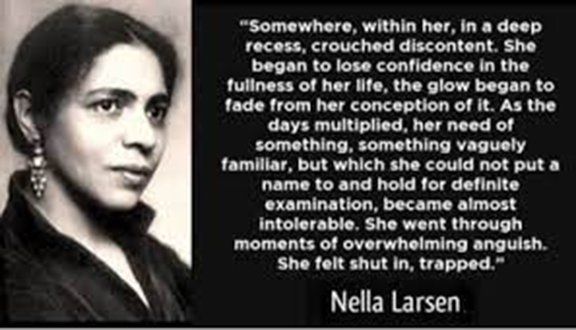

Let us end with the Nella Larsen passage at the top of this piece. Her direct, suggestive prose delivers the thought with a punch. It describes the debilitating effect of unrelieved discontent. “She felt shut in, trapped.” Larsen could be ascribing a closeted homosexual desire to her protagonist … or it could be something else entirely. That is the genius of her style. It’s visual, concrete, meticulously observant in its cyclorama of New York City and the mores of its inhabitants. Yet it also leaves room for interpretation. “Authors do not supply imaginations. They expect readers to have their own, and to use it.”

Well, we used it, Nella. Welcome to the Queer Harlem Renaissance.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.