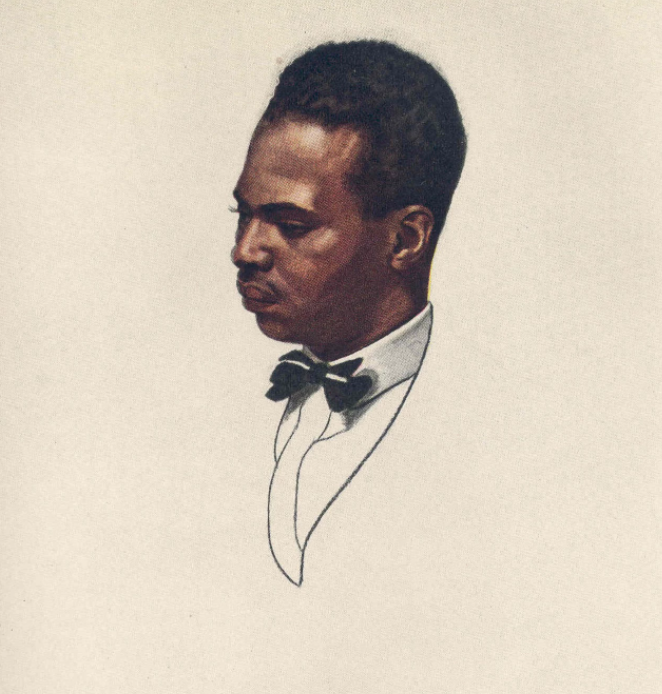

Gay Poet Laureate of the New Negro

By 1925, year one of the "official" Harlem Renaissance (at least as we define it), 22-year-old Countee Cullen was at the peak of his fame. From the time he graduated from New York's DeWitt Clinton High School, during his years at NYU, Cullen won numerous poetry contests, published in national magazines, and built a reputation that culminated in the publication of Color, his first volume of poetry. That same year he entered Harvard for graduate studies. Color was acclaimed by both Black and white America containing, still, some of his best-known and most anthologized poems. Its masterful use of traditional poetic form to express a contemporary Black sensibility, while not unique, resonated with both the literary Old Guard (W.E.B. DuBois) and acolytes of modernism (Wallace Thurman).

Given his fame and widespread appeal, Cullen became a star of what was then called the Negro Renaissance, continuing to put out books of poetry (less and less admired as time went on), editing an anthology of Negro poetry (Caroling Dusk), writing a regular column for Opportunity magazine, and winning a Guggenheim Fellowship which allowed him to live and study in France. Leaders and promoters of the Renaissance loved Countee Cullen and displayed him as one of the New Negro poster boys. The anointing of Cullen as New Negro royalty seemed to be sealed with his 1928 marriage to the daughter of W.E.B. DuBois, Yolanda.

The fly in the ointment lay in Cullen's sexual orientation. He was gay and entered into relationships with (white) men, mostly short-lived, throughout his life. He was anguished about being gay as a young man, but Alain Locke mentored him into an intellectual acceptance and even sent some sexual partners his way. Cullen tried to return the favor by introducing Locke to Langston Hughes, but that foray into gay matchmaking went spectacularly awry. There's justifiable speculation that Cullen's attraction to Hughes -- they had become friends early on -- contributed to a mysterious break in their relationship. And, of course, Cullen's sexual orientation insured the rapid failure of his marriage to Yolanda.

Try as he might to keep his gay affairs under wraps, other queer writers knew his sexual orientation. Thurman snidely referred to Cullen's wedding as a drag ball. In letters to her father, Yolanda all but said it outright, but W.E.B. affected a willful blindness--a common response to the "open secrets" of many of the prominent players of the Renaissance. (W.E.B. himself was quite promiscuous.) It's hard to know to what extent heterosexual Harlem knew or cared. Cullen was always discreet and in 1940 married a woman with whom he appeared to share conjugal happiness -- all the while carrying on a sustained affair with another white lover, Edward Atkinson.

Did Cullen write of homosexuality in his poetry? Not in any overt way. One can certainly apply gay readings to some of his verse, but these are interpretations. When race is the topic, specifically the burden of being Black in America, it is front and center no matter how elevated his rigid prosody and formal language (though fast becoming outdated).

Tropes of disappointment in love or sexual longing could be veiled in the misty allusiveness of the 19th-century Romantic poets he emulated. In our estimation, Cullen was a Black poet who happened to be gay.

You'd have to dig for a deeper connection.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.