Claude McKay's Bisexual Peekaboo

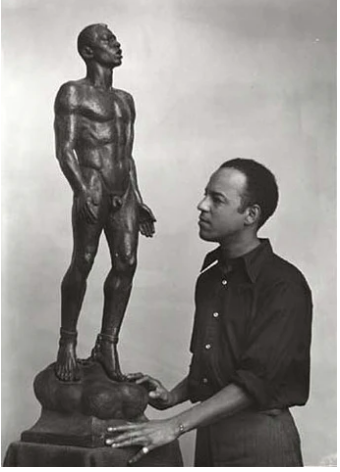

This intriguing headshot portrays a very complex young man destined to become, in spite of his physical absence, a star of the Harlem Renaissance. Claude McKay was a Jamaican who lived most of his life in America, a peasant and a poet, a literary innovator and an acolyte of traditional poetic forms, a radical, a late convert to Catholicism, a Black writer who quarreled and alienated practically all of the other Black players of the Harlem Renaissance.

He was also bisexual, although his homosexual adventures were known only to a narrow circle of acquaintances. And yet McKay's commitment to an honest presentation of his complex self and the world around him led him to portray his love of men plainly. You didn't need to "interpret" McKay to understand the valediction to a Black friend crushed by his difficult life in Harlem that closed the 1922 poem, "Rest In Peace.

'Twas sudden—but your menial task is done,

The dawn now breaks on you, the dark is over,

The sea is crossed, the longed-for port is won;

Farewell, oh, fare you well! my friend and lover.

His early poems, written in Jamaican dialect and based on his experiences in the constabulary, are equally straightforward about the passion he felt for a fellow policeman. "Bennie's Departure" speaks pretty plainly about "the love that dare not speak its name."

Because he was bisexual, McKay recorded and wrote about queer spaces and relationships in 1920s Harlem in a nonjudgmental manner. One of the sympathetic characters in his 1928 bestseller Home to Harlem was Billy the Wolf, "wolf" being Harlem slang for a masculine gay (which, of course, described McKay as well). Our short, "Congo Cabaret," made the queerness of this speakeasy explicit, but, once again, McKay's writing wasn't in the least bit coy. "I’se a wolf, all right, but I ain't a lone one," Billy grinned. "I guess I’se the happiest, well-feddest wolf in Harlem, Oh, boy!"

I could go on, but others have pointed out the strongly homoerotic relationships between McKay's fictional stand-in, the Haitian exile Ray, and the various "manly men" to whom he's attracted. (Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance.)

As McKay grew older, less able to contend with the poverty that dogged him all of his life, and grew more disenchanted and conservative in political outlook, he was more circumspect about his bisexuality, although he wrote a novel, Romance in Marseille, in the early thirties that depicted a loving relationship between two men with a remarkably post-Stonewall sensibility. His queer characters are not exotic or part of a gay subculture. They’re just ordinary working folks.

McKay was a passionate, complex, prickly writer and personality. The controversies that his writing stirred up upon publication turned on his radical politics and his unvarnished portrayal of a Black lower class that had no interest in aping the Victorian morality of the Negro middle class. They screwed and drank and fought and enjoyed the company of pansies and ecstatically lost themselves in music, dancing, and the various hues that melanin produced. McKay's unusual tolerance for his queer characters and the evident homoerotic heat of his best-known novels could get lost in the richness -- and strangeness -- of his writing. His mastery of Black dialect (there were, of course, different varieties) was as accomplished as Charles Chestnutt (way earlier) and Zora Neale Hurston (somewhat later).

Commentary from both Black and white readers flattened McKay's writing, although from different perspectives. But all ignored his peekaboo bisexuality until the rediscovery of Black literature and post-Stonewall revaluations of unknown or underappreciated writing allowed for an honest examination of McKay's contribution to both. (Romance in Marseilles, rejected by the publishers of McKay's other novels, smoldered in manuscript form until brought out just last year!)

To paraphrase McKay's best biographer, Wayne F. Cooper, "McKay never openly explored or publicly acknowledged homosexuality as an aspect of his personal life. . . As in other areas of his life, he remained . . . highly ambivalent about his sexual preferences and probably considered bisexuality normal for himself, if not all mankind."

During his life, few knew about McKay's homosexual proclivities. He was circumspect for the different times he lived in Harlem and was connected to the Renaissance during its glory years only by correspondence and the publication of his novels. Already a famous poet at the dawn of the Renaissance, his literary presence only grew with the success of Home to Harlem in 1928. He lived as an expatriate until 1934, and his homosexual activity, quasi-visible while he lived in Morocco was in Morocco. Secretive out of necessity, "unclubbable" to use the British expression (he belonged to no queer underground either in New York, London, or France), we nonetheless enroll the essential quixotic, flickering Claude McKay into the Queer Harlem Renaissance.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.