Africa As Seen From The Diaspora – 1922

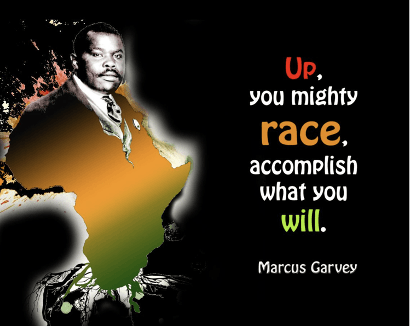

In terms of African American history, 1922 wasn’t particularly notable. Nor was there much to celebrate. A vigorous effort to outlaw the barbarous practice of lynching on a national level, the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, was scuttled in the Senate by Southern lawmakers. (Shamefully, a federal anti-lynching bill still hasn’t been passed!) Marcus Garvey’s gloriously delusional schemes for restoring Africa to the Black man (with, of course, Marcus Garvey as its emperor) began to sink literally (the dissolution of the Black Star Line) and organizationally (Garvey arrested for mail fraud).

There is a theme to tease out from the centenaries of 1922 if one is inclined to impose retrospective significance on unrelated events. Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association advanced notions of Black pride and Black unity – a diasporic consciousness – as no other movement had before. As an organizer and political leader, Garvey was a disaster; as an ideologue, mythmaker, and weaver of dreams, he was nothing less than epic. But for Garvey, as for the European colonizers he so decried, Africa was little more than a tabula rasa awaiting the imposition of Civilization. (Check out the history of Liberia for the 19th-century version of that “Negro” arrogance.)

Up until the 1920s, most African Americans were either vaguely or pointedly ashamed of their African origins. They were only taught what the white man had preached: that the Dark Continent had yet to shed its infantile savagery and that Africans had contributed nothing to Civilization.

And this brings us to another centenary, the publication of Harlem Shadows by the poet Claude McKay. McKay is a complex, contradictory, sometimes tortured writer, not always consistent in his views on race, literature, and ideology but always in the vanguard of writers who were dealing with the larger perspectives the 20th century made available to African Americans. In 1922, Harlem Shadows preceded the Harlem Renaissance, announced the Harlem Renaissance, and fertilized the Harlem Renaissance by inspiring the younger writers who followed.

McKay was born and raised in Jamaica and didn’t encounter America until he came in 1912 at the age of 23. Having grown up in a majority-Black colony where the racial hierarchy was maintained by ideological state apparatuses (government and education) rather than by violence, McKay had learned something about ancient African glory. He speaks of this in the Harlem Shadows poem entitled “Africa.” Yet the final lines of this sonnet sadly echo the Western ignorance of his ancestral land.

Honor and Glory, Arrogance and Fame!

They went. The darkness swallowed thee again.

Thou art the harlot, now they time is done,

Of all the mighty nations of the sun.

But through this Western-imposed gloom, there comes a glimmer of light. In 1922, Professor William Leo Hansberry of Howard University teaches the first course ever in African history and civilization.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.